Pennsylvania winters are notoriously cold so that many historical sites shut down for a few months. As you know, I enjoy writing about history, so I saved this story about the Joseph Priestley House in Northumberland, Pa from a visit I actually made in November. I knew virtually nothing about Priestley at the time except that my husband recommended the outing, but when I heard that he "discovered" oxygen, I realized that he was a pretty big deal.

|

| The Priestley House |

Priestley was a man of many talents. He immigrated to the United States from England in 1794 and was known as a clergyman, philosopher, scientist and educator. It's not as if Priestley started out life with a silver spoon in his mouth. His mother died when he was young, so his father placed him in the care of his sister Sarah Keighley, who had no children of her own. Mr. and Mrs. Keighley were Nonconformists, refusing allegience to the Church of England and therefore raised Joseph under Calvinist theology.

When Joseph was 11, one of his first experiments was to observe how spiders could live in bottles minus a change of air. When he became older, he studied for the ministry at the nonconformist Academy at Daventry in Northampton and impressed the administration so much that he was excused from the first year's work and half the second.

When Priestley left Daventry, he accepted a position as a minister in a small church in Suffolk, England. This stint didn't last long due to his views. (Today he would be referred to as a "Unitarian Universalist.") Priestley found that he enjoyed working with students and later accepted work as a tutor at Warrington Academy in Lancashire, before marrying his wife Mary Wilkinson, starting a school and introducing science into the curriculum. His essay on "A Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life,"soon became the outline of grammar school education. Priestley also developed a Chart of Biography and a Chart of History, which was printed many times over the years. These endeavors earned him an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Ediburgh.

These successes inspired him to write a history of discoveries in electricity. By this time, Priestley had met Ben Franklin, who was in England on business related to Pennsylvania. Franklin encouraged Priestley in his ambitious endeavors by providing him with pamphlets and other printed materials to assist in his projects and the two became life-long friends.

By 1767, Priestley had left the Academy to become the minister at Mill Hill Chapel in Leeds. While there, he carried out his first experiments on gasses, which led to the creation of the soda water we drink today.

In 1772, William Petter, second Earl of Shelburne, approached Priestley to offer him a position as a tutor for his children and a librarian for his estate. He accepted and was extremely productive as a chemist during this time likely due to two reasons: Lord Shelburne provided the money to purchase equipment and supplies and Priestley's new job just wasn't very demanding.

During this time, Priestley identified more than a few gasses, like ammonia, nitric oxide, oxygen, sulfur dioxide hydrogen chloride and more, but, once again, his Unitarian Universalist religious views were frowned upon and were an embarrassment to Shelburne and the two men parted ways. Priestley then went on to accept jobs, mostly as a minister, but life in England became difficult as he dealt with the consternation of the community. On July 14, 1791, the second anniversary of Bastille Day, came the Birmingham riots. Mobs of dissenters put off by Priestley's attacks on the doctrine of the trinity burned Priestley's church and his house. Priestley lost everything, including his manuscripts and library in the fire. By 1793, his sons decided they'd had enough and set off to America, buying land located between the two branches of the Susquehanna River near the Loyalsock Creek. The headquarters for the 300,000-acre settlement would be 50 miles away in Northumberland. Priestley must have missed his three sons, because just a year later he decided to join them. It turned out to be a good move and Priestley was welcomed warmly by Pennyslvania society.

In his memoirs, Priestley wrote that Philadelphia may have been more desirable to some, but it was very expensive and he thought that his sons might be less prone to temptation and more industrious in Northumberland.

By 1794, he had chosen for his new home a property overlooking the Susquehanna River, but progress went slowly since the fresh-cut wood needed to be dried. The slow building process set the project out three years and the sad part is that his wife passed before she could enjoy her new house.

|

| A sitting and sleeping area. |

|

| The parlor of the Priestley House. |

According to records, Priestley discovered carbon minoxide at that time, which he obtained by passing steam over heated charcoal. He also learned that salt, when mixed with snow, contained nitric acid. Priestley then went on to write a total of 30 papers on scientific experiments while in Northumberland.

|

| The open-hearth kitchen of the Priestley residence. |

|

| The commodius dining room of the Priestley House. |

|

| A bedroom in the Priestley House. |

Because his faith was so important to him, he wrote more than a dozen theological books as well.

Priestley died in 1804 and his son Joseph Priestley, Jr. and his family lived in the home for a time before returning to England. Later, Priestley's grandson took up residence in the home.

When Priestley's grandson put the place up for sale, Seth Chapman, President Judge of the Eighth Judicial District (Northumberland, Luzerne and Lycoming counties), bought it and lived there until his death. It was later purchased by Rev. James Kay, pastor of the Unitarian congregation in Northumberland, who also resided in the house until he passed. The home then went through a series of owners before becoming a boarding house for railroad laborers, at which time it became neglected and run down. This caught the attention of Dr. George Gilbert Pond, Professor of Chemistry and Dean of the School of Natural Sciences at Penn State, who contacted his students and alumni to pool their funds to prevent destruction of the historic house. Pond had big plans to deconstruct the house and relocate it to the campus grounds. Unfortunately, Pond passed before his plans came to fruition. Later, the Dr. Pond Memorial Association decided instead to restore the house and build a fireproof museum for Priestley's books and equipment.

|

| The fireproof museum which contains Priestley's documents and equipment. |

|

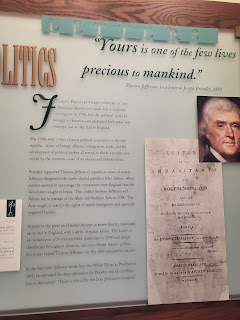

| An exhibition that greets guests at the Visitors' Center. |

Those who may like to take a tour of what has been called "a Mecca for all who would look back to the beginnings of chemical research in America," can do so in the spring. Tours of the house are conducted March through November. The Joseph Priestley House can be found at 474 Priestley Avenue, Northumberland, Pennsylvania.